When you’re in comics, or art in any capacity, you are carrying on a long tradition of putting thoughts, concepts, and commentary to image and using those images to convey complex thought. The earliest records we have of human existence focuses on art and art objects, and so we have several thousand years of influences from which to choose from. From cave paintings in France to petroglyphs in North America or desert lines on the Atacama plains, us comic artists have been laboring away for countless millennia. As a child I remember being transfixed by my first glimpses of Egyptian tomb paintings, and watching the colorful marvel of a Pharaoh’s life unspool before me, preserved in rock:

This poor guy probably got promised “exposure”.

This poor guy probably got promised “exposure”.

So since an artist is shaped by their history, and their art is influenced by the forebears they study, I will go ahead and list here some of my artistic influences over the years that have led to BOHICA Blues:

Charlie Brown & the gang (Schultz apparently hated the name “Peaunts”) was a huge influence on me as a child. I had a natural talent towards illustration and loved comics, and the “Peanuts” characters were simple, expressive, and reliable– comforting things for an early cartoonist’s mind. While the dialogue & subject matter frequently veered into clunky but bewildering philosophical paths that I didn’t fully understand, rather than be turned off, it gave me something to strive towards.

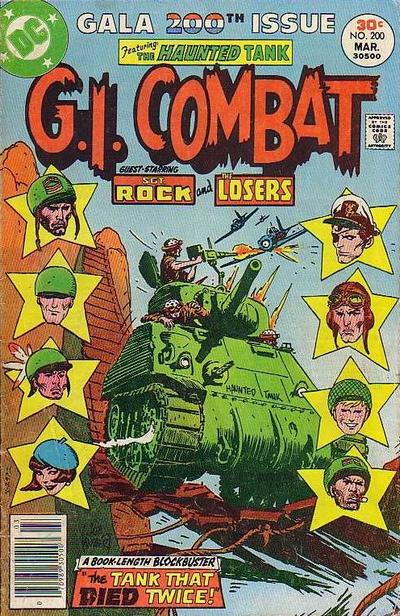

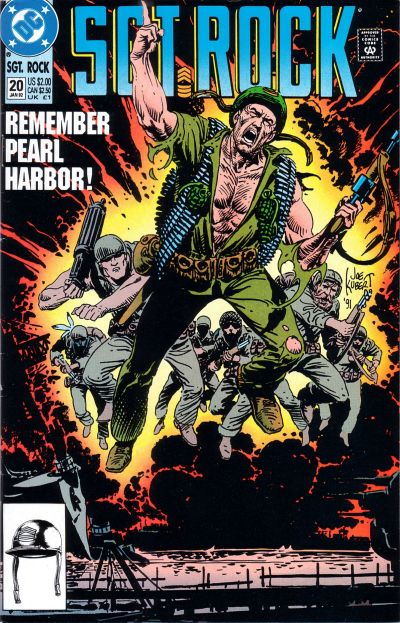

I had seen American comics dominating store shelves, almost entirely devoted to superheroes. I was never a big “fights & tights” fan and didn’t see the appeal. A refreshing alternative was DC’s line up of World War Two action comics. World War Two is a favorite of American entertainment due to the opportunity for moral clarity offered by that war, something that is highly unusual in most wars. Of course, even World War Two had a lot of grey areas in it, though, and while I loved the action (and lack of silly guys in fluorescent mantyhose running around), I eventually realized how thin the stories were when it came to confronting the historical realities of the era. Still a lot of fun, though.

I’d heard of and occasionally seen examples of European comics– Tintin and Heavy Metal, for example. I was intrigued, but what really got my attention was Judge Dredd, from 2000 A.D. Judge Dredd is a member of a brutal, no-nonsense police force in a post-apocalyptic city-state called Mega City One. The 2012 movie with Karl Urban did a good job portraying it; don’t bother reading the toe-tag for the Stallone version back in the 90’s. Judge Dredd was great because I got to see a really big, popular comic tackling big issues without patronizing the audience. For me, it represented someone who shattered the “Superhero ghetto” that imprisoned most American comics.

Redfox, on the other hand, was a fantasy sword-and-sorcery adventure that did not last very long, but made a deep impression on me. From 1986 to 1989, it lasted but 20 episodes before Fox and Chris Bell set it aside. When the series started, the art was a little better than I could produce on a good day of hard work and patience– it was something I could see myself doing, if I put my mind to it. But what really impressed me was how the art improved dramatically over the arc of stories. Just by drawing, constantly, the art grew by leaps and bounds. I realized I could do the same thing. And while I go on about the art, the story as well was fantastic. Dialogue, characters, plots– and the big payoff was that when a main character died, he actually stayed dead, and his friends that survived had to grieve and adjust without him. No cheap tricks to keep someone alive– real loss. Unheard of at the time.

About the same time I was discovering the above-mentioned British comics, I had also discovered a ragged old copy of this 1978 book by G.B. Trudeau of “Doonesbury” fame. In this book, the main character arc is of Mike Doonesbury, Mark Slackmeyer, and Joanie Caucus and youthful adventurers that set out on a cross-country motorcycle voyage of the United States. I think it was from here that I learned to slide into political humor and social commentary, neatly wrapped up in a handful of panels while carrying a larger story.

In the 1990’s, I met a number of people who actually did comics for real. I went to conventions and got to see what happened to get a comic from idea to page, and interact with the people who made it happen. I enjoyed the military science-fiction aspects of “Albedo” and realized there was a market for such things; I also got to watch Stan Sakai’s “Yusagi Yojimbo” go from being a hobby to gaining a lot of mainstream popularity outside the Superhero genre. I realized you don’t need to be magic or rich, or even completely wired down tight (in fact, it helps to be a bit off kilter to do this stuff), just be willing to actually do it.Easily, the biggest eye-opener this ended up being, for me, was realizing that comics didn’t have to be the “big guys” with a wealth of resources– for any niche or interest out there, there could be a book for it.

But one huge influence that paid off later was Donna Barr’s “The Desert Peach”. While a lot of artists I knew fussed about having the “right” tools, pens, brushes, a certain shade of ink, exact-weight paper harvested from the trees on the shore of a mystical lake in the Tibetan mountains, and other resources, I’d watch Donna Barr grab, literally, a ballpoint pen and a piece of ordinary typing paper and churn out her next comic chapter in a couple hours. Years later, in the Iraq desert, I remembered that ability to work with any resource and not to let excuses come between me and getting a project done. While I admit I prefer certain tools and resources, all I truly need is pen, paper, and lots of coffee.

The TV show M*A*S*H was hugely popular in my teen years. It combined serious topics about war and human nature, but with a lot of comedy. The show was ostensibly about an Army medical unit in the Korean War, but everyone knew what it was really about– Vietnam. It had an ensemble cast (mostly spread out over years, not so much featured all at once) with a lot of recurring minor characters, and many episodes could stand alone although there were running story arcs and themes that came up from time to time. M*A*S*H ran for 11 years, which nestles nicely with Vietnam’s 10 years, the Iraq War’s 8 years, and the Afghan War, which is currently in it’s 15th year as this is written. The themes talked about are still applicable today, I’d wager.

A strange and probably unexpected inclusion, I have to admit I was not a regular watcher and only saw, at most, maybe a dozen episodes, and those mainly by chance. However, I liked the way the show’s creators would have the characters’ imaginations intrude in the show, as bizarre scenes, hallucinations, and fantasies would play out in momentary vignettes. The characters were eccentric and almost completely unhinged while ostensibly working at a serious job (a law firm). It had a surreal Far Side kind of element to it, I felt, and I wanted to use some of that in BOHICA Blues as characters fantasized or hallucinated during their long time in Iraq. In M*A*S*H they devoted one whole episode to a series of dream sequences, where the personnel of the 4077th were sleep-deprived and hallucinating– but in Ally McBeal, they made it a regular part of the routine to delve into characters’ subconscious or imaginations. In BOHICA Blues, people or landscapes will change shape to fit another person’s perceptions, spiritual or mythical beings may appear, and yet “normal” life will go on afterwards without interruption.

“The Far Side” has been mentioned, and it is an influence as well. Gary Larson’s bizarre and warped humor was well-received and showed just how far down a rabbit hole the reading public was willing to go.

“Calvin and Hobbes” probably comes as no surprise; the philosophical dialogue and Calvin’s leaps of imagination fit in well with the BOHICA Blues mentality.